Localization and Ace Attorney

Nov 21, 2014 // Janet Hsu

Question: If you were going to localize a comical game with a lot of Japanese humor where you play as a lawyer and you have to defend some pretty zany characters, how would you do it: 1) direct, literal translation from the Japanese 2) some localization — maybe change some names and some of the material 3) total localization — including making changes to some of the graphics if you have to — to the point where it’s no longer recognizable that this game is from Japan.

That was just one of the questions I was asked at my interview for this job that I have now held for 9 full years, and one that I have asked myself every time I sit down to localize any game, but especially an Ace Attorney. My answer then is still the answer I would give today — it would largely depend on the story and how it plays out — but since then, I have added one more general criteria: it also depends on how much the localization would contribute to the overall enjoyment of the game, because crafting a solid yet nuanced localization is no less important or daunting of a job as a level designer crafting a stage for you to fight your way through. Given how complex games have become with HD graphics and elaborate voice overs, localization touches every aspect of a game, from its story to its user interface to its audio tracks and its visual design, which is all tied together through its programming. I covered some of the technical details in my “ making of Dual Destinies ” blogs, so today, I thought I’d cover some of the more theoretical and academic aspects and concepts of localization. For the sake of this discussion, I’m very broadly defining localization as “any tweaks or changes made to the source material and/or the process by which source material is adapted for the purpose of making it more relatable to a target audience”.

I joined Capcom Japan’s fledgling localization team in mid-November, 2005. By then, the first Ace Attorney had already been localized. Because of the time zone difference trick in the first episode, there was a need to decide on where the game was going to take place. Thus, the localization team of PW:AA had already picked the direction of the localization for me — total localization. And while that decision has left me with a teeny-weeny dilemma for every game after that, I still feel that moving the setting to AU Los Angeles was the right choice to make because I think it helped make the characters and their dialogue more relatable to a wider audience. But not only did it make them more relatable, it also made it easier to convey the same emotional experience that a Japanese player has while playing Gyakuten Saiban to a Western player playing Ace Attorney. I’ll go into more depth about what I mean by “emotional experience” in a bit.

For now, let’s take a step back and start with something that I think should be pretty obvious: No translation can ever be 100% the same as the original – by the very nature of converting one thing into another, all translations are the product of someone’s interpretation. In fact, I encourage you to try it out for yourself with this little thought experiment.

How many different ways can you summarize what is about to happen to Phoenix in this scene?

Out of everything you came up with, which ones sound like something a criminal would say? Or how about a soccer mom? Now, take the variation that sounds most like how you would say it, and write another version that sounds like how your best friend would say it. Even though you and your friend are probably of the same background and culture, you might still say things slightly differently, right? But are either phrasing wrong? Do you think the way you phrased it would be the same as how the original artist would have phrased it?

In essence, translating between languages is like that experiment – translators take a shared experience in another language and try to put it into words another person who speaks a different language will understand, but because of differences in the way people perceive things and their life experiences, different people will phrase things in different ways. That’s not to say that inaccurate translations are acceptable, because translations that convey completely different information are never acceptable; it’s just that there are many ways to express the exact same thing in equally accurate ways.

So if even translations themselves are not without translator bias (and even some reader bias when the translated text is read and digested in the reader’s mind), how can a translation, let alone a localization, without any interpretation possibly exist? Which leads me to the heart of the matter: if all translations already involve some degree of interpretation, then what is localization? What is the point of it?

Remember when I said earlier that inaccurate translations are never acceptable? Well, that’s one of the big ways in which translations and localizations differ. Translations are not concerned with how the reader will feel or react to the information. The primary objective of a good translation is accuracy. However, as a piece of entertainment, the stories in games are primarily concerned with the feelings and reactions, or the “emotional experience”, of the player in its original language, and therefore, any localization must strike a balance between what is “textually accurate” and what is what I call “emotionally accurate”. Let’s take an easy example from last-last week’s blog .

Mmm… Grilled chicken skin on sticks…

Recall the bit about grilled chicken skins on skewers (torikawa/ã¨ã‚Šã‹ã‚) and how Mr. Takumi wrote about it as if it was the most normal thing in the world. Most Westerners would balk at me if I offered them grilled chicken skin and either think “Eww, gross!” or “Okay… Not something I would eat but…” But to Japanese people, it really is as every-day as it sounds in that segment. So even though I translated the blog more literally by preserving the yakitori reference, did it give you the reader the same emotional experience as a Japanese reader? Probably not. In other words, that blog was translated to be “textually accurate” regardless of how “emotionally inaccurate” some parts of it may have been to the reader.

“But what about games like the Persona series?!” I can hear some of you already asking. While I think they do a wonderful job of localizing the series, I personally feel that because their primary audience is people who are already more familiar with Japanese school life than the average Westerner, the localization is closer to the translation end of the scale than the full-on localization end. The degree to which they localized the setting and text is probably something the Persona localization team thought long and hard about before they decided on their current direction (because the very first Persona was a very different beast !). Still, as someone who has played Persona games in Japanese, even I can’t say I feel super nostalgic at the same points as my Japanese friends because I didn’t go to school in Japan — even if I can intellectually comprehend why those things would feel nostalgic to them.

Case in point: What is this?

If you answered, “A kindergartener’s name badge!” then congratulations! You know a thing or two about Japanese schools! If you answered, “Oh wow, that reminds me of kindergarten!” then congratulations! You probably went to one in Japan and are feeling nostalgic now! If you answered, “ Tofu on fire !” then congratulations! You probably have no idea what this thing is and are probably not Japanese. As these articles point out, Japanese netizens had a good laugh at the description “tofu on fire” for this simple emoji that they took for granted to mean a kindergartener’s tulip-shaped name badge, with some people expressing nostalgia at just seeing a picture of one.

Funny enough, in that emoji link, you can see that Microsoft took the liberty of localizing the emoji into something a Westerner would very easily identify as a name badge! (For some bonus background on why a lot of your smartphone’s emoji are super-Japanese, check out this nifty article .) And what about that chicken skin example from earlier? If I had “localized” that into a food like pork rinds/pork scratching or maybe even fried calamari, Westerners would’ve probably had a similar, if not the same range of reactions to it as the Japanese audience to grilled chicken skins.

So now comes the big question: Who cares? Why bother to make the overseas versions “emotionally accurate” at all? Well, if you are a player who doesn’t care about experiencing the game in the same way as a Japanese player, then I suppose a nuanced localization isn’t as important to you. But for most people, I think there are a number of big benefits to be found in a more full-on localization, including broader appeal, immersion, a sense of enjoying the game in the way the creator intended for it to be enjoyed, and a more meaningful experience overall.

First up: broader appeal. I don’t think I need to say much more than “What creator wouldn’t want as many people as possible to enjoy their game?” and for that to happen, the game has to be something people can just relax and play for fun. For fans, broad appeal is a good thing because that means it will be easier to convince others to get into your favorite games and play, thereby creating more fans with whom you can talk to.

Some of you may not believe me when I say this, but when I sit down to localize a game, I really do think of all of you fans — a range of people that goes from purists to expats living in Japan to people in their 30’s and 40’s living in anywhere but Japan with kids who are asking them to play AA games on their iPhone with them. Yes, that is quite a large variety of fans, which is why emotional accuracy will pretty much always trump textual accuracy in determining whether something needs to be localized or not for broader appeal. Broader appeal also grants the benefit of allowing people to feel more fully immersed in the game because the game world will seem more relatable to them.

With each new entry into the series, I’ve had to do some world building in my head to keep things consistent. One thing you learn as a writer is that internal consistency in your world is a very important factor in how cohesive and believable it is. So even though in the real world, spirit channeling is not real, it certainly fells real enough in the Gyakuten Saiban/Ace Attorney worlds by the time you’re playing the third game to have a real emotional impact because the rules for that aspect has remained constant all throughout the series.

Having said that, I’ve never really had the chance to talk at length about the localized version until now, but I realized very quickly after Dual Destinies that I needed to address the issue of immersion, which is why I wrote about it a few weeks ago. To me, the world of Ace Attorney is as much of a game mechanic as yelling “Objection!” into the microphone for this series. If the lore behind the world was not being properly conveyed and was interfering with people’s enjoyment of the story, then I felt I had to address it like any other gameplay flaw in any other game. However, with AA being the lighthearted series that it is, there will probably never be a chance for me to directly state the exact conditions of the alternate universe that I’ve been working off of in the games themselves. Still, a number of things can only be possible in a world where Japanese people were allowed to own land because the California Alien Land Law of 1913 was never passed… Or I guess if Japan took over America or if America lost WWII, but why does everyone jump to such negative thoughts when an alternate universe can come from the alteration of any factor you choose, including the negation of discrimination…? Which leads me to another thought: I wonder if people who start playing Ace Attorney after they’ve seen the movie version of Big Hero 6 will have an easier time accepting Japanifornia simply because they’ve seen something else that features a similar mash-up of cultures…?

Anyway!

Another benefit to a good localization is that it will be truer to the intentions of the original creators than a strict translation by allowing a Western player to be entertained by it in the same way the creators intended their Japanese players to be entertained by the original – you’re laughing at the same points, and crying your eyes out at the same points, too.

Nothing is worse than going to a Japanese movie theater with a group of Japanese friends and being the only person to laugh at a joke that no one else in the group (or the entire theater, for that matter) gets because the joke doesn’t translate at all, even with subtitles. Trust me, all expats have experienced this at one point or another, and it makes me a little sad sometimes at just how much my Japanese friends are missing out on when they watch a Hollywood film.

In fact, this feeling of “missing out” is something Japanese developers have come to realize over time as they play games localized into Japanese. Compared to Japanese to English localization, English to Japanese localization is still in its infancy, and it shows at times with disastrous results. Since they have come to experience what bad localizations can do to a player’s sense of immersion, many Japanese game creators have started treating localization more seriously than in the past and have been encouraging less literal translations of their games in favor of localizations that speak to the target audience and provides them with the same experience as the original. To me, this makes localized games and dubbed movies unique when compared to, say, subtitled movies because we really can re-create the full experience through localization.

Speaking of the creator’s intentions, creators are also generally not actively trying to offend people, so when something that is culturally offensive in the target audience’s country is left unlocalized, it can actually be a disservice to the original game, in my opinion. But even then, a balance must be struck. As an example, there was some debate on the localization team of Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney over the use of the word “panties” to describe Trucy’s magical bloomers. On one side were the people who felt that it was socially and culturally inappropriate from an American point of view to joke about panties in relation to an underage girl, regardless of the fact that the panties actually turn out to be a pair of massive, blue bloomers. On the other side were the people who felt that the joke would be lost if players knew from the get-go that they were looking for massive bloomers. The argument I made for emotional accuracy was that the Japanese version was purposely trying to lead a Japanese player into feeling unease at looking for a pair of what they might imagine to be “sexy lingerie”, so the payoff is the sense of relief that the player feels along with Apollo when he finally finds them and realizes they’re just a prop for her magic show. If I had gone along with the other side and allowed Trucy’s Magic Panties to be localized as Magic Pants, the only people who might have gotten the same experience as the Japanese might have been the British players because “pants” means “underpants” in British English.

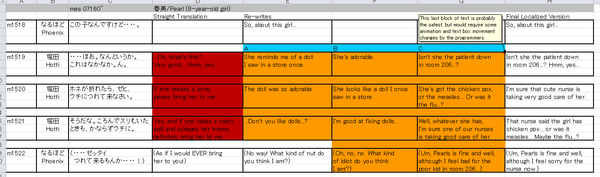

Even still, there have been times when the original Japanese dialogue was simply too over the line. I’m speaking of course, of everyone’s favorite lecherous fake doctor — Director Hotti. To say nothing of what he says about Mia, which, while not necessarily taboo, was definitely skirting that line between a T and an M rating back in 2006, if you show Dr. Hotti a picture of Pearl in AA2, episode 2, he says some pretty average-sounding things on paper that become three text boxes of “Absolutely Not!” when combined with his grabby pervert animation.

From my original “What do we do???” file…

You’ll note that in suggestion C, I was thinking of changing the animations altogether to further reduce the ick factor, but unfortunately, the team was unable to change the animations for the localized version, so a text rewrite where Hotti’s lechery is directed at an adult nurse was the option we chose to go with. Does this count as “censorship”? Maybe. But again, creators are not out to offend their players either.

Japanese humor related to pedophilia and perversion is calibrated to a very different standard than the one we use in America. No one in Japan thinks that pedophilia is great or even OK. In fact, people are usually very upset whenever there is an article in the newspaper about a schoolchild who’s been abducted or found dead after being abducted. But how a culture chooses to deal with these sorts of issues is up to that culture, and in Japan, it’s still OK to have lecherous characters to laugh at in order to defuse some of the harshness of reality. But don’t ever mistake that for wide-spread approval because the perverted characters that hit on little girls are never the good guys and are always the butt of jokes or the bad guys or play some other negative role. In this case, the punchline and real knee-slapper part comes from Phoenix’s very strong reaction against Hotti, who serves as the “silly set-up character”. When thinking about it in the cultural context of Japanese society, the original Japanese is wildly perverted, but is still funny to a Japanese person. In America, the original would have just been sickening to a lot of people regardless of how the last line played out because it’s not something we joke about in the same way at all.

But let’s say I had wanted to use suggestions A or B, which are still super creepy to me even now, I would run into another one of the things that define the boundaries of decency in localizations: first-party requirements and the ESRB/PEGI rating boards.

It’s well known that Nintendo used to have extremely strict guidelines as to what games released in the West could and could not contain. Among these things are references to religious terminology, leading to SNES versions of FF4 and FF6 to rename “Holy” elemental to “Sacred Power” and “Pearl” respectively. Now, does this constitute censorship? Perhaps it would be considered that now, but back then, it was a part of the localization changes Nintendo required in an effort to make their games more palatable to a wider audience. As time went on and social values changed, Nintendo obviously relaxed their policies as well. The same goes for the ESRB for what they classify as T-rated content and M-rated content. Even still, we had to err on the side of caution in this case because as Ted Woolsey once said , “Any time you submitted a game to Nintendo you had to … submit the print out, the entire screen text, the ROMs and do all that stuff and give it to them and they’d spend time going through it. If you had something [inappropriate] like that, that stopped the submission you were in trouble. It was very expensive and you could miss your deadline to ship.” This is still true today.

So you see, localization is a messy and complicated process that involves the good judgment of not just the translators (who are often also the initial localizers because they localize the text as they go along) and editors and testers and game designers and programmers and artists and sound designers and first-party submission leads, but also first-party companies like Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft, and ratings boards like the ESRB and PEGI.

Bringing all of the previous points together, ultimately, what a good localization does is provide the player with a more meaningful experience because the player will be fully immersed and focused on the story, not on being busy looking things up or merely intellectually understanding something. I generally play games in their original languages (English-language games in English and Japanese games in Japanese) but I will play exceptionally well-localized versions of my favorite games. Time and time again, the superb localizations of games like Super Paper Mario and Virtue’s Last Reward leave a greater impact on me, and I react more fully from the gut simply because those games have been fine-tuned to resonate with my own upbringing and by being in my native language.

In closing, I feel truly blessed to have heard so many positive responses to the localized world of Phoenix and company. I know full well that it’s unusual for people to like, let alone accept, such drastic changes to the source material, so I can only hope it’s because people consider the localization to be good.

There is just one more thought I’d like to leave you with. I think there is a very big difference between writing to people and writing for people. Writing “to” people simply means you are writing what people want to see. There’s nothing surprising or unexpected to be experienced for the reader, and it can sometimes lead to people feeling like the work is too “over-produced” or “fake”. On the other hand, writing “for” people means that you should write not to people’s expectations, but to what is truly entertaining, all the while, keeping what people like in the back of your mind. It’s a lot like picking out a present for a friend. You can simply give them something they’ve been saying they want for years, or you can think on your own about what that person likes and pick a present that you think they will treasure. Sure, the latter is a bit of a gamble, but the payoff for everyone when you picked well is bigger and more meaningful, isn’t it? In a sense, that is the essence of not just good localization, but of all game design. A good director of any aspect of a game will know their audience well enough to make the right decisions and pick that perfect present.

I suppose it’s only natural that game directors, art directors, sound directors, programming leads — these people who have been integral to game development for years — have built up a sort of “default” level of trust and respect from the players, and that, unfortunately, due to the uneven experiences with localizations Western players have had in the past, many people have taken on a stance of distrust and negativity towards localizations and localization teams as their default. But I’m asking you to please take a moment to reflect on the hard work that all localization teams have placed into Western releases, and especially your favorite Japanese games. There are many battles that take place behind the scenes that I can’t go into here, and I can only speak for games I’ve worked on, and yet, the stories I hear from friends who have worked on localizations of major franchises for other companies line up with my own. While I can’t deny the twists and turns the art of localization has taken to get to where we are now, I have seen with my own eyes over the past 9 years, just how big of a leap in quality Japanese to English localizations have made overall.

As for the future of this series in terms of its localization direction, I guess the final question that only you can answer for yourself is this: “Do you trust me as its localization director?”

———————-

Next time, I’ll be sharing some closing thoughts from Mr. Takumi as he wrapped up the production of Trials and Tribulations. I promise it won’t be as giant of a wall of text as this entry has been!

Until then!

Catch up on previous blog entries here!

-

Brands:Tags:

-

Loading...

Platforms: