When gameplay and narrative get along

Oct 05, 2014 // GregaMan

Hey guys: remember Resident Evil on the original PlayStation? Let’s talk about it.

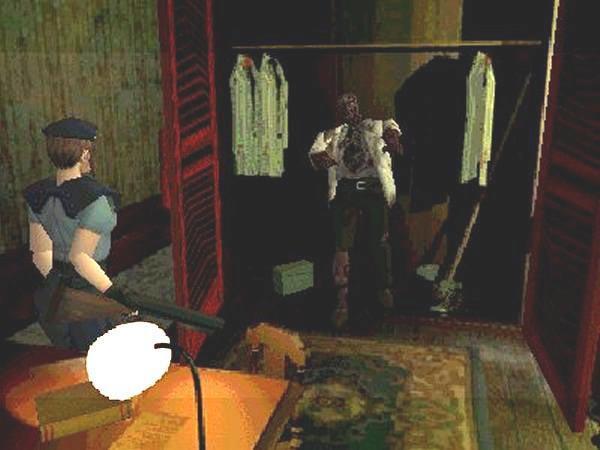

In its time, Resident Evil was considered groundbreaking for placing both player and character in a highly restrictive scenario with very true-to-life rules and consequences. Characters—and players—were required to keep track of and maintain supply of their ammunition, healing items, and more as though they were real-life commodities. It may be hard now in this age of narrative-driven, realistic games to fathom that that was ever a remarkable thing, but remember that RE came at the tail end of an age where virtually all video games were action platformers instilled with zany dream-world logic, where items were intangible icons obtained by running full-speed at them and bullets were giant yellow balls that spewed endlessly from your guns with perfect, unwavering trajectory and impossibly fast firing rates.

↑ We used to just not ask questions.

In Resident Evil, bullets came in bullet boxes. If you wanted to fire bullets from your gun, you had to find boxes of bullets, stop, pick them up, load them, and then properly ready your gun to be fired. Furthermore, shooting an enemy in the head would produce a different effect than shooting it in the torso, would produce a different effect than shooting it in the legs. It was up to the character—and player—to aim the gun at the desired body part for the desired effect. All of these things were groundbreaking in that, despite the preestablished lunacy of the video gaming medium, they all made logical sense. Given the narrative scenario presented by the game, even (nay, especially) someone who had never played a video game before might have assumed that any or all of these elements would be in play.

↑ Nothing could top this level of realism.

And so it was in this way that Resident Evil was, for many video gaming enthusiasts of the 1990s, the most immersive game ever, placing players more thoroughly in the shoes of a protagonist (two, actually) than any game they had experienced before it. Whether players were conscious of it or not, Resident Evil marked a new milestone in what would come years later in certain erudite circles to be known as ludonarrative resonance.

I understand if you find that word to be daunting—even the word processing software I’m using to write this, whose sole job is to process words, didn’t recognize it. Likewise, I understand if you think the word is pretentious: “I ‘on’t never needed no lu-do-na-ree-tive resomacation to teabag your momma last night!” you may be thinking. Rest assured, there is a whole separate essay to be written on the teabagging phenomenon. But also rest assured that ludonarrative resonance is just a fancy—and handily succinct—way of saying “that thing where the game gives you a good reason for doing the stuff you do instead of just arbitrarily slapping rules and objectives together.”

If you’re unfamiliar with this idea, I recommend you check out this essay by Escapist forum-goer Jezixo. But I’ll try to summarize it here as succinctly as possible.

The “ludo” aspect of a game is its “gameplay”—the things you can and can’t do as the player; the ways you interact with the game, as dictated by its rules, including its control scheme. Virtually every piece of interactive entertainment has this, however simple. The “narrative” is the greater context provided for those rules and actions, be it through cutscenes and text, or simply the “skin” of the game itself&mda**** graphics, sounds, and music. Mega Man, for example, without its “narrative,” is just a game about a square hitbox rising, falling, and shooting out little pellety hitboxes at other square hitboxes that disappear after contact with X number of pellets. With its narrative, which is primarily conveyed via simple graphics and sounds, it’s about a noble robot boy jumping around and blasting other robots created by a mad scientist bent on world domination. In Mega Man’s case, the narrative is simple, but pretty crucial to the player’s motivation. Otherwise it’s just a convoluted set of arbitrarily rules you have to memorize.

“Ludonarrative,” then, is the combined interaction of these two elements of games, and “ludonarrative resonance” is when those two elements are in harmony—that is, in Jezixo’s words, when “the player is allowed to do things and given a strong reason why they should do them.” This is the opposite of the more oft discussed “ludonarrative dissonance,” which is when, to again borrow Jezixo’s words, “the player is allowed to do things which they are only given reason not to do, or disallowed from doing things they are only given reason to be able to do.”

If, for example, a game’s cutscenes portray the protagonist as someone averse to physical violence, but the “gameplay” segments encourage you as that protagonist to murder dozens of people, the so-called ludo and narrative elements are dissonant with one another. How much that matters is of course up to each player to decide, but I do feel that this dissonance is often what’s at work when people describe a game or aspect of a game as “video gamey.” It seems to be something that avid gamers just accept about games, but that can alienate people less familiar with the medium. “They just spent ten minutes of exposition establishing you as a noble samurai and now you’re beating up the locals and taking their money!”

↑ “You told me these wings were legendary, and now I find you dying horribly?!”

Nowadays, most games are made up of ludo and narrative components that are sometimes resonant, sometimes dissonant. Returning to the Resident Evil example, consider how the game goes to great lengths to establish a very real-world philosophy toward possessions: namely, that they are finite commodities that take up space, are exhaustible, and scarce. This is both an aspect of the Resident Evil narrative (i.e., Jill and Chris, trapped in a mansion, must scavenge for supplies and be selective in which ones they carry) and an integral gameplay system (i.e., you must scavenge and be selective). In this sense, the ludo and narrative are resonant—the player has a convincing reason for doing the things he or she is required by the game to do. After all, Jill and Chris only have so many pockets. And it’s not like they knew there would be

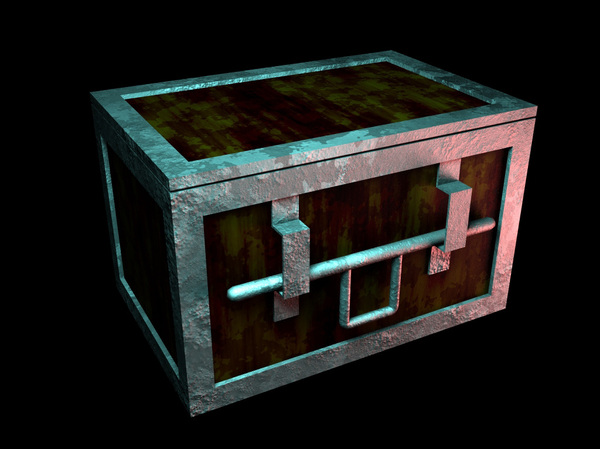

At other times, however, players are required to suspend disbelief. Certain “safe rooms” scattered throughout the game contain item-storing chests. Inexplicably, an item stored in one of these chests can be retrieved later on from a separate chest in a separate room, as though the chests are all connected via some magical item vortex. As far as I’ve witnessed, most players seem okay with this. The game is convincing enough overall, and this this one concession the game offers is such a boon to the player, that it proves to serve the greater good with no substantial drawback. The designers might have been able to come up with a more convincing narrative for the system if they’d tried, but given the technical limitations of the time and the unobtrusiveness of the simple box system, albeit magical, they probably just bit the bullet. I’m no pro designer, but I can’t think of a better system that would have worked on the tech and preserved the solitary atmosphere of the game. Besides, the box has since been embraced by the Resident Eviling community as one of the “video gamey” charms of the earlier games.

↑ The item box may have been a crack in RE’s realistic facade, but it’s hard to complain when it’s so damn helpful.

At any rate, I think that sort of shows how games can have a combination of resonance and dissonance between their “gamey” and narrative elements. Sometimes games are gamey, and that’s okay! But I do think the video gaming medium is at its most interesting and admirable when those two elements are in harmony.

Thinking about it, Capcom has actually explored this harmony in some interesting ways over the years, both big and small. The following is a list of cases some colleagues and I thought up, but I wholeheartedly encourage you guys to contribute your own in the comments!

- Devil May Cry 4 – The Red Queen.

If you haven’t played Devil May Cry 4, I hate you. Just kidding. But I do recommend you play it. Nero, the game’s newly introduced protagonist, wields a sword called the Red Queen, which unlike most swords, can be revved like a motorcycle engine. Revving the sword with perfect timing during an attack causes it to power up the subsequent attack, which can in turn be revved to power up the next attack, and so on. To rev the sword, players press the L2 button or Left Trigger as Nero in the game does pretty much the exact same thing, flicking the sword handle’s trigger. This is reflective of a recurring element I have noticed in Capcom design, which I call “tactile resonance” or “haptic resonance.” I’m not sure if there already exists another term, but what I mean is that the actual control input, the action the player literally does with his or her hand—which, to be sure, is part of the “ludo”—is designed to resonate with the on-screen action, which is an element of the narrative. As an example of ludonarrative resonance it may not be as deeply integrated as Resident Evil’s survival concept, but it’s a pretty neat idea. Consider how rare it is for a controller input to have any meaningful correlation with the character’s in-game movement. On a PlayStation controller “X” is usually Jump, but that’s a tradition rooted more in ergonomics than in a desire to mimic the act of jumping on a controller. In other words, no game’s narrative ever gives you a “good reason” that a button with an “X” on it should represent jumping.New innovations in input methods such as motion and touch control have led to something of a proliferation of this concept, but I feel it’s still rare for a game to do it as classily or with as much respect for precision as Devil May Cry 4.

Recent shooters have adopted a tradition of using a controller’s “triggers” to replicate the real-life sensation of pulling a gun trigger (and indeed the triggers themselves have become more trigger-like over the years), and yes I feel this would be another example of “tactile resonance.”

- Monster Hunter (the first one) – Attacking with the analog stick.

The original Monster Hunter on the PlayStation 2 was a quirky, quirky game. Man was it quirky. If you’re a newer fan of the series, you may not know that you originally had to use the right analog stick to perform attacks. In the history of video games, Jet Li is the only one to do that and live to tell about it. But Monster Hunter gave it a go! The relevance here is in the fact that the stick motions sorta kinda mimicked your avatar’s weapon motions. This was most apparent with the Great Sword: tilting the analog stick upward would cause the avatar to perform an upward slash; tilting left would activate a horizontal slash. I wish I could say that the tactile resonance extended beyond that, but the many weapons of Monster Hunter were simply too complex and nuanced to be express fully with a rubber-tipped knob. I do like to imagine a world where switch axes are controlled with transforming controllers, but for now I’m happy with the reliable clickiness of traditional button inputs. - Okami, Okamiden — Drawing stuff, being a deity.

Okami on the PlayStation 2 presented another simple example of “tactile resonance” with the celestial brush mechanic, wherein players draw certain symbols with a magical in-game brush by mimicking the brush’s motions with the analog stick. The resonance was debatably enhanced even further through the use of the Wii and PS3 versions’ motion controls, such that players were able to actually wield the controller like a brush in their hand. But I feel the tactile resonance truly hit its peak with Okamiden on the DS, where players were able to literally draw the desired symbol on the screen with a stylus. We even released a brush-shaped stylus for full effect. It’s a simple idea, but another rare case in which the player and in-game avatar are performing nearly identical acts.

More interesting still is the deeper ludonarrative resonance the brush mechanic presented on a conceptual level. Think about it: In control of a divine avatar (the “mother to us all”), the player is able to freeze time at will and manipulate the two-dimensional game world with his three-dimensional “brush” as simply as one manipulates a painting by adding new strokes to it. The player with complete cross-dimensional control over the game world is not unlike the all-powerful, transcendent deity presented in the game itself. In some sense, a person playing a game is perhaps always comparable to a deity in that he or she is exacting control on a world from outside that world’s confines, not to mention the fact that the player has the power to shut off that world at any time; but only in Okami do both the narrative and the ludo highlight that idea.

- Steel Battalion – The entire freaking idea.

Steel Battalion on the original Xbox was, it seems to me, the comically uncompromising culmination of the tactile resonance concept.I say this with utmost respect for the work and as a proud owner of that rad, rad Steel Battalion controller. But think about it: The game holds that tactile resonance with such importance that no traditional controller would do. Instead, they created a one-to-one replica of the in-game cockpit controls that cost $200 at retail and included two control sticks, multiple pedals, and about forty light-up buttons.

According to the game’s Wikipedia article, one of the primary objectives of Steel Battalion as stated by producer Inaba-san was to show “what can be done in the game industry that cannot be done in others.” I feel that the gaming medium shines its brightest when it creates these ties between player action and narrative context, and I suspect that that belief was at the heart of Steel Battalion’s development.

- Street Fighter – Street fighting.

I touched upon this in my blog about the many parallels between Street Fighter and Monster Hunter, but there’s an incredibly clever bond in the Street Fighter series between the in-game narrative context and the psychological experience players have when at the helm against a human opponent. On a psychological level, Street Fighter matches are incredibly similar to the experience of actually engaging in a martial arts bout, and I’m confident that anyone who’s partaken in both will agree. Just as Ryu and Ken would actually have to read and manipulate one another’s psychology, so too do the players. Moreover, the special moves in the game mimic the actual experience of practicing specialized martial arts techniques that require precise execution in order to be effective. It’s simple and it’s brilliant: The narrative depicts two people having a fight; The ludo requires that two people have a fight.

- Dragon’s Dogma – The Ur-Dragon.

Dragon’s Dogma is in fact full of unique examples of ludonarrative resonance, from the way its Pawn Sharing mechanic is explained narratively to the story’s cyclical nature which coincides with subsequent playthroughs. But to me the most interesting example, perhaps on this entire list, comes in the crusty, purply form of the Ur-Dragon.

For the sake of this topic, I will talk only about the online version of the Ur-Dragon. For the uninitiated, this battle in the game differs from all others in that it is an asynchronously cooperative experience that incorporates all other online Dragon’s Dogma players. Narratively, as the Ur-Dragon phases into the dimension of a given Arisen, so too does he manifest in that corresponding player’s game, presenting a boss battle. All damage done by the player to the Dragon in a ten-minute span is tallied up, and the Dragon flies off, phasing into some other dimension (i.e., another player’s game) to face another Arisen, whose contributed damage will in turn be added to a grand total.

Once again, the ludo aspect and narrative aspect are in resonance, which, yes, is probably an easier thing to achieve when the story deals with magical, mysterious beings since you can explain away crazy gameplay mechanics with an equally crazy narrative and no one will call foul. But the game’s acknowledgement of the existence of many concurrent Arisens spanning an equal number of dimensions means that its narrative takes into account the fact that multiple people bought Dragon’s Dogma. That, after all, is the only way that the Ur Dragon story makes sense. In fact, the more people who bought and played the game, the more damage is done more quickly to the Ur-Dragon.

This, in my mind, goes beyond ludonarrative resonance into something I’ve never even heard of before—like, I don’t know…resonance between the game’s market success and its narrative. Weird, right? For the record, more than 420 “generations” of Ur-Dragon have lived since the game’s release in spring of 2012. That’s a whole lotta asynchronous cooperation.

↑ Rare footage of the online Ur-Dragon actually dead! - Dead Rising – Doin’ it your way in the zombie apocalypse.

Dude, you could write a whole essay on how Dead Rising is relevant here. In fact, I did. In short, it’s a game with a setting, but it’s “about” whatever you say it is. We love Dead Rising ‘round here.

I know I say this at the end of every one of these mammoth posts, but phew! I, for one, am exhausted. So now it’s your turn! I want to hear your examples of times when a game’s “ludo” and “narrative” components are in glorious harmony. It could be big, integral things, or little bitty things like the way Mega Man’s charge buster is executed by holding and releasing a button as though holding and releasing the shot itself—I think that counts!

Or if you don’t have any examples but just have some feedback on this here post, I welcome that as well! Thanks for readin’! <3

-

Brands:Tags:

-

Loading...

Platforms: