More words on the art and science of localization

Aug 29, 2014 // GregaMan

A new episode of the Capcom Unity Official Podcast went live last week, and the topic was localization. To me, localization, words, and language are such fascinating topics that I found the task of cramming everything into a less-than-one-hour-long show extremely daunting. Inevitably, we did not get through everything worth saying about the topic, nor even everything I’d planned in my seemingly manageable episode outline. But I hope you give it a listen anyway.

The reality is that you could go on about localization virtually forever. I would be thrilled if our localization team ever had its own regularly updated blog, but for now we do try to highlight their excellent work and insight with guest blogs here on Unity. If you haven’t checked out Janet Hsu’s latest Ace Attorney localization blog or Andrew Alfonso’s enlightening series on Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate, do yourself a favor and do those things.

Meanwhile I did want to supplement the podcast with a few more of my own thoughts for those with a deeper interest in the subject. This gets a little esoteric, so only read on if you’re a language person. Don’t worry, you won’t be missing any title announcements or new details on Rad Spencer’s mustache phase if you skip it.

So yeah.

I, for my part, and for the record, have never worked on game localization. But I do come from a linguistic background and have translated a lot of things, from novels to comics to countless other odds and ends, including business correspondence and hundreds of blog posts here at Capcom. And I submit that with two languages as far apart as Japanese and English, all translation is inevitably part localization, meaning that there is always an element of free interpretation and tailoring involved. If you just convert words to their dictionary-equivalent words, you end up with gibberish–and you need look no further than Google Translate to witness that for yourself.

↑ o.O

There is always an element of subjective interpretation involved. That ends up making the process inherently somewhat risky, since one man’s, woman’s, or even team’s interpretation of the essence of a work could differ a little or a lot from that of any number of belligerent superfans. But you never know until the work is out there.

At the risk of sounding harsh, I want to take this opportunity to point out the misguidedness of many purists out there—the kinds of people who immediately correct you when you say “anna-may” instead of “ah-nee-may,” never stopping for a second to remind themselves that the word anime is itself a corruption of the English word animation, nor that that word has in turn been co-opted by the western world to refer specifically to Japanese animation in a rare case of double-reverse-Engrish (in Japan, it simply means “animation”), nor that the Japanese language is uncompromising in its assimilation of loan words, mercilessly altering them to fit its limited sound set and katakana syllabary, meaning that ironically, the supposed purist act of painstakingly mimicking the pronunciation of a word from a foreign language is a particularly un-Japanese tendency . Try as you might to cover up, your culture is showing.

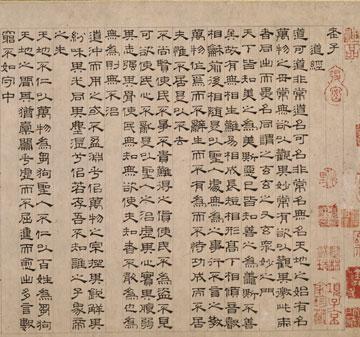

But wait, don’t go. I’m not trying to insult people who like pronouncing foreign words the way they sound in their respective languages. If you like saying “ah-nee-may,” say it! But I encourage you to be tolerant of those who don’t. Remember: We all view the universe through our own eyes, and that’s a neat thing. Also, all language is made up by random people anyway. When I was telling my pal Andy about the concept for this blog post, he pointed me to the Tao te Ching, noting that Chapter 1begins by pointing out the inherent impurity of words:

“The Tao that can be talked about is not the true Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal Name.”

Naturally, translations of the above passage itself vary wildly from one attempt to the next, exemplifying the very point the words are asserting.

“Any dao given by language is not a constant dao. Any labeling given by words is not constant labeling.”

“The tao that can be described is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be spoken is not the eternal Name.”

“The tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name.”

↑ Even this version is with its flaws.

Even things like how the word Tao is spelled and whether or not it is capitalized vary from one interpretation to another. It makes you think—what if Phoenix Wright had been named, like, Leviathan Gotchanow? It’s just as “right” as “Phoenix Wright” (but admittedly not as Wright).

Okay okay okay, I’ll reel it back in.The point I want to emphasize is that, because Japanese and English are so fundamentally different, more often than not there is no such thing as “a” “correct” translation. It’s simply not a binary thing. At its simplest it’s an inexact science; at its most complex, it’s an art. Usually it’s some degree of both.

Here’s an example I think anyone can understand even without a background in Japanese. Let’s take the Japanese word ã†ã‚‹ã-ã„ (urusai). This word is an adjective, which means it is used to describe nouns. In a literal sense, the word means “annoying” or “loud.” It can mean either. In practice, however, the word is also often used as an exclamation in a way almost identical to how an English speaker would use the expression “Shut up!” That is, you yell it when you want someone to stop being annoying or loud. Hence, the most common translation for the word urusai when it is exclaimed in Japanese, is “Shut up!”

But that’s not the literal translation! If we were being completely uncompromisingly faithful to the original Japanese, the “correct” translation would be “Annoying and/or loud!” But try yelling that the next time you want someone to shut up, and you will quickly realize that you are a boob. Someone will probably also subsequently tell you to shut up. You boob.

Naturally, the door swings both ways. Seemingly simple words in English often don’t have perfect Japanese equivalents and must instead be spread across a multitude of different Japanese approximations in various contexts. Check out the comically long entry for the word get on the awesome Japanese-English dictionary site SPACEALC.

The point is, in order to coherently transfer Japanese to English at all, you have to be unfaithful to the original Japanese, to a degree. You routinely have to abandon things like parts of speech or literal meaning.

But this leads down a deep rabbit hole. Consider this: Is “Shut up!” the only thing someone can exclaim in the above situation? Couldn’t you also translate it as, say, “Put a sock in it,” “Quit yer yammerin’,” or–my personal favorite–“Crammit”? Why yes, you could. And depending on the voice you are trying to convey, you should consider all these options before putting a pen to paper. It is in this way that translation and localization inevitably come down to the sensibility of the person doing the work. It is also why localized game text often appears to have lots of liberties taken–this is all done in the name of preserving not the words of the original work, but the essence, as perceived by the creators — and to avoid sounding like Google Translate at all costs.

Naturally, this creates a factor of risk. On the podcast, we brought up the example of Nibelsnarf, which is the localized name of Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate’s Hapurubokka. This more than any other localized name seemed to have fans scratching their heads, and in some cases making a bit of a fuss.

“That’s not what this thing is called! It’s not even close!”

Well, maybe not at face value . But even the made-up words of Monster Hunter are designed to elicit an emotional response from an audience of a specific cultural background. And when you switch audiences and cultural backgrounds, retailoring that name design is what it means to “localize.” Whether it is “right” or not is up to each player to decide, but it’s worth reiterating that these name changes are made with the original development team’s input. Personally, I like Nibelsnarf. But there’s always a risk that some people won’t share the sensibility projected by the localizer–especially with an audience as broad and disparate as all of the western world .

↑It is said that at one point the team toyed with the idea of giving the Nibelsnarf an ironic mustache and Mumford & Sons T-shirt for the western version to help bridge the gap, but the idea was later dismissed as “Hapuru-bogus.” (OMG this is a joke please don’t report on this please)

As another example, take a look back at the ending of Mega Man 7. Hoo boy. We still hear about this one from time to time. If you haven’t seen it, the gist is that Mega Man gets Wily cornered after the most grueling Wily battle ever (seriously), and then in a shocking display, threatens to kill Wily at busterpoint, suggesting for the first time that Mega Man may have actually had free will all along even though it had previously been established that the key difference between him and X was that only X had free will—hence the name X, which referred to the algebraic variable; a symbol of his limitless potential—his “X factor,” if you will.

Here’s that ending in English.

“I don’t trust you, Wily! I gonna do what I should have done years ago!!”

“You forget, Mega Man. Robots cannot harm humans…”

“I am more than a robot!! Die Wily!!”

Now in Japanese (skip to 1:35).

Here’s the most literal-but-coherent translation I could muster for the same part above.

“I won’t be tricked anymore!”

“You’re going to shoot? Shoot me? You, a robot, shoot me, a human?!”

“……”

↑ Japanese ellipses are actually always translated this way.

Note the discrepancy here. While he brandishes his buster at Wily in both versions, the Japanese Rock Man simply falls silent while the English-speaking Mega Man explicitlymakes a threat on Wily’s life, almost seeming to revel in his own murderousness. There are an awful lot of ways to interpret the reasoning behind this change. Anthony Birch formerly of Destructoid once wrote the following musing on the subject:

“In the Japanese Mega Man 7, the original Mega Man is just a Pretty Cool Guy who, despite being a slave to his programming, is a decent enough dude. In the American version, he’s basically Bruce Willis. Or Neo. Or both.

I’m curious as to why this change was made: is it a cultural thing? Coming from a history of emperors and faithful samurai, are the Japanese more likely to be okay with a hero who, despite lacking free will, is still a good man? Comparatively, are the capitalist, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps-or-some-such**** Americans so focused on the individual that a mechanically impotent hero would just be too much of a bummer? I can’t say for sure as I’ve obviously got nothing to go on other than my own cultural stereotypes, but it is, perhaps, worth thinking about why the American localization team decided it’d be fun to arbitrarily turn Mega Man into a murderer.”

I’m not so sure I agree with the assertion that Rock is a “slave to his programming” in the Japanese version; that’s just one interpretation of an ambiguous scene. Unfortunately I’m not here today to clarify this point of ambiguity. It wouldn’t be fair to the people who were too bored to read this far. Besides, a little ambiguity is healthy in this age of instant gratification, with your Taylor Swift and your hashtag-yolo and whatnot. It’s not like Mega Man actually killed Wily in the English version, and in fact he lays down his buster arm in both versions.

Localization was a far less sophisticated and collaborative process back then, but I do think Birch is correct that the discrepancy probably had a lot to do with a perceived difference in audience and that audience’s value set. Remember that this was still in the heyday of the western world’s love affair with quip-spouting action heroes. It makes sense that they would want a bold line of dialog there for the western version rather than a delicately ambiguous moment of silence. Especially given just how terribly grueling that Wily fight was. I’m sure the difference seemed innocuous at the time—“Japanese people like silence and ambiguity, western people like clarity, one-liners, and badasses.” In broad strokes, that may be kind of true ^^;; But also, this was back when games were treated a lot like other playthings, so the integrity of the narrative with regards to the overall brand canon probably wasn’t held with particularly high priority, though I couldn’t say for certain since I was like eight at the time.

Of course, years later we see how the discrepancy between versions has spurred ongoing philosophical debate that will probably never be settled, and in turn how that exemplifies the risk presented with localization. Luckily, awareness of that risk is mucher greater amongst publishers nowadays, and that is part of why localization is now such an elaborate, thoughtful, time-consuming, and yes, expensive process.

Phew. Well, I think I’ve said more than enough on the subject for one blog post. As usual, here’s hoping this was enjoyable for someone out there. Let us know, otherwise I’m just gonna keep doin’ these!

-

Brands:Tags:

-

Loading...

Platforms: